Essential woodworking toolkit

One of the most common questions I read and hear about woodworking is “what tools and machinery do I need to get started in woodworking?”. It’s a tough question to answer because it depends on what area of woodworking you want to get into. You may be interested in box making, pen turning, bowl turning, carving, furniture making, built-ins, garden furniture, shed building or even timber framing. The essential woodworking toolkit needed is vastly different for each.

Your choice of tools will also depend on your budget and whether it’s for a hobby or a commercial operation.

If you’re reading my blog, then you’re probably not a commercial operation. So let’s assume you’re a hobbyist or wanting to build up a small business making items at the higher quality end of the spectrum. I will give you some ideas to enable making a wide spectrum of projects.

Tool sharpening isn’t included in this article, but you will need equipment to sharpen your tools. I have written an entire article on sharpening edge tools.

When you’re starting out, you want tools that are versatile and can perform many kinds of operations. Some tools are super versatile, and others are a one-trick pony. You will find my choices for essential tools below. You’ll find my luxury tools after them, so make sure you read on.

Essential safety equipment

If you want to continue to enjoy woodworking then you need to stay safe. Losing an eye or a limb, having difficulty breathing or suffering from dermatitis is not an outcome anyone wants. Make sure you use guards where possible, use push sticks or push pads and wear appropriate PPE. Be sure to add these safety items to your essential woodworking toolkit.

- Safety glasses / goggles / face shields

- Push sticks and pads

- Dust extraction

- Respirator mask

- Gloves

Safety glasses / goggles / face shields

Some operations in the woodworking workshop are seriously hazardous to your eyes and face. Often you need to get close to see what you’re doing, but that puts your eyes in harm’s way. Especially if you’re using power tools, turning on a lathe, but also for things like carving. Wearing safety specs, goggles or a full-face shield could save your eyesight. Keep them in a zip-loc bag and clean them regularly.

Push sticks and pads

If you value your fingers, you’ll want to keep them away from moving machinery. That’s saw blades, router cutters and planer (jointer US) heads. Some will take a limb off cleanly, and the wonders of modern medicine will be able to stitch it back on, although it may not work afterwards. Others, such as a planer head, will mince fingers to a pulp and there’s no recovering from that.

Make a variety of good push sticks that will keep you away from saw blades (table, bandsaw etc) and router cutters, and use push pads with non-slip bases with planer (jointer US) and spindle moulder (shaper US) machines. I found that grout floats with the soft orange/red spongy rubber bases are the best.

Dust extraction

The one thing you’ll be glad of more than anything else is a decent dust extraction system. It’s far better to remove the dust hazard at its source than have to wear a respirator and clean up all the time. Whether it’s a powerful shop-vac or a blower with a vortex separator and a fine dust filter will depend on your budget. Get the best you can afford.

Respirator mask

COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is a thing, a serious thing in woodworking.

“The outlook for COPD varies from person to person. The condition cannot be cured or reversed, but for many people, treatment can help keep it under control so it does not severely limit their daily activities.

But in some people, COPD may continue to get worse despite treatment, eventually having a significant impact on their quality of life and leading to life-threatening problems.” Source: NHS

Wood dust, or worse MDF dust can get breathed deep into your lungs, but once there your body can’t get it out. So essentially you end up drowning in sawdust, literally. For any operation that generates dust that you can’t collect at source, you should wear a respirator.

There are varying filtration levels for respirators, in the UK you want FFP3 and in the US you want N95. Try a few different brands and types because fit is very important. Oh, get a shave, beards don’t make good filters.

Clean your respirator after use (remove the filters first) and keep it in a ziploc bag. So it doesn’t get all dusty and dirty.

Gloves

When you’re using finish or other shop chemicals. Whether it’s glue, shellac, mineral spirits, danish oil, polyurethane etc. it’s best to wear nitrile gloves. They’re impervious to most chemicals, tend not to tear easily, and allergies are rare. Dermatitis is not pleasant.

Gloves are also good for when you’re working with some high-tannin woods, such as white oak, so you don’t end up with black-stained fingers.

Essential layout and measurement tools

I used to be very precise with my measuring, but over the years I’ve gone away from super accurate measurement in favour of transferring measurements from piece to piece. They’re measured, but not with “units” as such. Sure, I work to rough dimensions, so I may make something that’s roughly 12” long by 8” wide with ¾” stock. However, the ¾” stock may in reality be 18mm (as that’s what we have here in the UK). The 12” may be 11 15/16” and the 8” width may be 8 1/32”. It’s not really that important, so long as it looks right, fits where it needs to fit, and the pieces are sized relative to each other.

Reference faces and squareness are the most important factors in the way I make things. My layout and measurement tools in my essential woodworking toolkit are:

- Marking knife

- Pencil and eraser

- Square

- Marking gauge

- Rule and tape measure

Marking knife

This is something I use almost every time I enter the workshop. It needs to be sharp. I like a diamond point marking knife, but some folks prefer a single bevel. It’s whatever works for you.

Pencil and eraser

If you’ve read any of my plans, or other articles, you’ll know that I’m a huge advocate of the marking knife. However, that doesn’t mean I believe there is no place for a pencil. Pencils are great for marking up faces and edges, roughing layout and numbering parts. Get an HB (#2) pencil or softer. Hard pencils will dent your timber, especially if you’re working with softwoods.

You should also pair your pencil with an eraser, preferably one of those with a white end for paper, and a grey/blue sandy end for wood.

A pencil sharpener is a luxury. I like those big old-fashioned school ones with a handle.

Square

A top quality square is one of the most important tools you can own, so don’t skimp on this. I have a Starrett 6” combination square and frankly I can’t fault it. I also own a Bridge City try-square and it’s also good but not as versatile as the Starrett. Yes, I know Starrett combo squares are expensive, but they are worth every penny.

There are quite a few inferior quality squares out there, even ones marketed as “premium”. So beware and make sure you check anything you buy.

Depending on the scale you work at, you may want a bigger square, 12” or 18” combination squares are readily available. Bigger than that and you’re getting into the realms of construction scale, and so not really in the scope of this article.

Marking gauge

This isn’t something you need to buy, you can make one fairly easily. The only real issue is getting a suitable blade if you want to make a cutting gauge.

Pin gauges are for marking with the grain, cutting gauges are for marking across the grain, but both work in both situations. Given the choice of only one, I would go for a cutting gauge every time. The mark is much cleaner and better for dropping a chisel into.

If you’re buying a marking gauge, then get a wheel cutting gauge, they’re great. The cutting wheel on the end of the beam gives a real advantage for marking workpiece thickness and transferring depths of mortises. I like the Veritas ones because the wheel is sharp and their action is smooth and they lock solidly. My first was the “micro adjust” type with gradations, but I wouldn’t bother with those features again. The plain and simple wheel marking gauge is fantastic.

Rule and tape measure

It always amazes me when I see a rule in inches with 1/10 graduations. The beauty of inches is that they divide elegantly when graduated as ½, ¼, ⅛, 1/16, 1/32, 1/64. Let’s say you have a piece that’s 4 ¾” wide and you want the centre. 2 ⅜” is so simple to work out, just halve the whole and then double the denominator. You almost needn’t think. Make it decimal, and it becomes a mess. 4.75” becomes 2.375”, it’s not mega difficult but you’re now working to thousandths of an inch.

In woodworking I advocate working in feet and inches, but some people are much more comfortable with millimetres. That’s their choice.

Whatever your choice of measurements is, get the best quality steel rule you can afford in that measurement. I like my rule to have no lead-in, so I can accurately align the end with the edge of my workpiece (inside or outside). If you work in inches don’t get a rule with metric gradations, it won’t be exactly 12” long and will ultimately annoy you.

Another longer rule is also an excellent investment, something like 24” or even 36” (600mm or 1m). Alternatively, you can always use a long story stick.

I’m not a fan of tape measures, but they’re handy for rough work.

Essential work-holding

This segment of woodworking is often overlooked, but in many respects it’s more important than almost anything else. If you don’t have something to put your workpiece on, or to hold it still, it is impossible to make things.

- Workbench

- Bench hook

- Shooting board

- Quick clamps

- Parallel-jaw clamps

Workbench

Do you go for a big, solid, hand-tool woodworkers workbench, a multi-function table, or a lightweight portable work bench? Well, it depends on what you’re making, where you’re making it, and how you are working. Whatever you go for, you don’t want it to be flimsy.

Hand-tool woodworkers workbench

These are big, sometimes as long as 8’ (2.4m), heavy and very sturdy. Ideally they don’t move when you are planing, sawing or chopping. The tops are usually very thick and heavy, with work-holding mechanisms built in. So you’ll have bench dogs, possibly a tail vise and a face vise.

Whether you need one as a beginning woodworker is debatable, I’ve been woodworking for about 35 years and still don’t have a proper workbench. I have been designing and building my ideal workbench for the last 17 years. I now have a bench top with some work-holding features.

Sjöbergs make good quality, and affordable workbenches if you don’t want to make your own. There are other makes, but you can trust the Sjöbergs ones to do the job well.

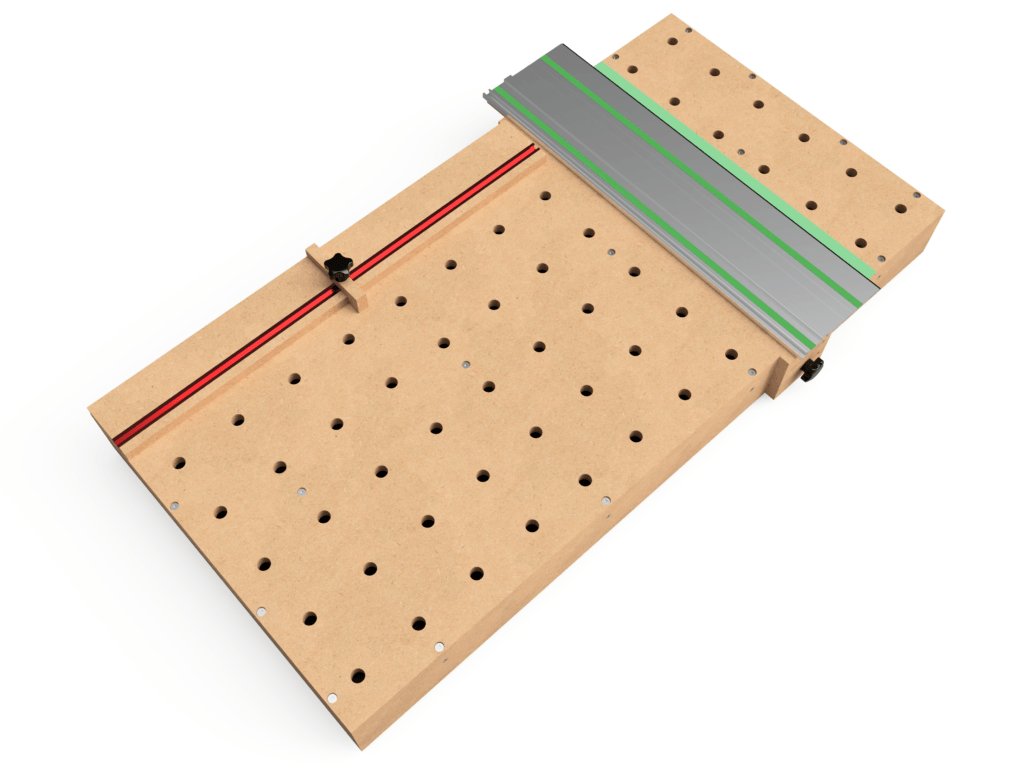

Multi-function table

If you have a home workshop and you want to make things, then there is little that can beat a multi-function table (MFT). MFTs typically have an array of dog holes and some way of working effectively with a track saw.

You can use them for assembly. They’re not suited to heavy-duty chiselling, like chopping out mortises, but for light duty work should be adequate. You won’t have a vise, but there are other ways of clamping workpieces.

I’ve written an article and produced plans to make your own MFT table, it’s not difficult and will save you a lot of money. If you want a commercial MFT, then the Festool MFT is the original and probably the best one around.

Portable workbench

Black and Decker popularised little fold-up, portable work benches with their WorkMate product. They usually have a twin screw vise, a few dog holes and metal legs. Some are better than others. I have a cheap, nasty one, which I upgraded with some 1 ¼” thick oak tops once the terrible MDF ones failed. The advantage is that they are very portable, and when used in pairs can be quite practical on a job site.

Saw benches

Usually found in pairs, saw benches are at just below knee-height (custom fit to your knee) so you can hold your work with your knee while you cross-cut or rip-cut. The height and positioning creates an almost perfect sawing action. Most woodworkers make their own saw benches, it’s a nice simple project for beginners and you’ll have an essential piece of work-holding kit that you can use for years to come.

Bench hook

You probably won’t find these in any store, but a bench hook is a really useful piece of kit for any woodworker. It helps you to hold workpieces while you make cross-cuts at the bench.

If you’re using a western style saw, you hook it over the edge of the bench nearest you as they cut on the push stroke. If you’re using a Japanese style saw, then hook it over the far edge of your bench as you cut on the pull stroke. You can also cut mitres into the fence, and it’s a good idea to have two of the same thickness so you can support longer workpieces.

Shooting board

A shooting board is essential if you want to make the ends of your workpieces square or accurately bring them to a specific dimension. Especially useful when preparing timber for joinery operations, which often rely on the workpieces being square to each other.

I’ve written another article about shooting boards, and you can also get free plans for my shooting board here.

[convertkit form=1350613]

Quick clamps

Popularised by Irwin, these one-handed clamps are a game-changer for most solo woodworkers. For holding things in place while glue sets, or you saw something, or any of a multitude of other uses, these are essential kit. I have a variety of makes and types, ranging from 12” & 48” Irwin Quick-grips, 6” Solo clamps, and 14” Klemmsia cam clamps.

Parallel-jaw clamps

The parallel-jaw clamp or F clamp is handy when you’re gluing up a workpiece. They’re also good for work-holding too. I often use them in lieu of a vise to clamp workpieces to my bench top. I like the Bessey ones, but there are other quality brands available.

Essential hand tools

Some hand tools get used far more often than others. Some are essential to get things done even if you don’t use them all the time.

The most used tool in my workshop is probably my #4 smoother plane. Mostly because it touches almost every surface. Whether it should be part of the essential woodworking toolkit is questionable, though. You could use other planes to do the same job, or even a sanding block (if you don’t mind the dust). I’m going to include it as an essential tool though. If you work with hardwoods, then there’s almost nothing better than a planed finish.

For making things that go together, you’ll need these tools.

- Panel saw / Hand saw

- Dovetail saw

- Fretsaw

- ½” Chisel

- Mallet

- #4 smoother bench plane

Panel saw / Hand saw

Often the fastest and simplest way of breaking down your timber is to use a panel saw. You can go for either re-sharpenable premium saws or a cheap hard-point mass-produced saw. I’ve never owned a re-sharpenable panel saw.

The hard-point saws I buy are reasonable quality, they can’t be sharpened but have hardened teeth which stay sharp for quite a long time. For the amount, and type of hand sawing I do, I find they’re good enough. I try to find ones that are comfortable in the hand, and have a pitch suitable for cross cutting. I tend not to rip by hand, so around 9tpi works well for me. For the price of one re-sharpenable saw I can buy around ten hard-points.

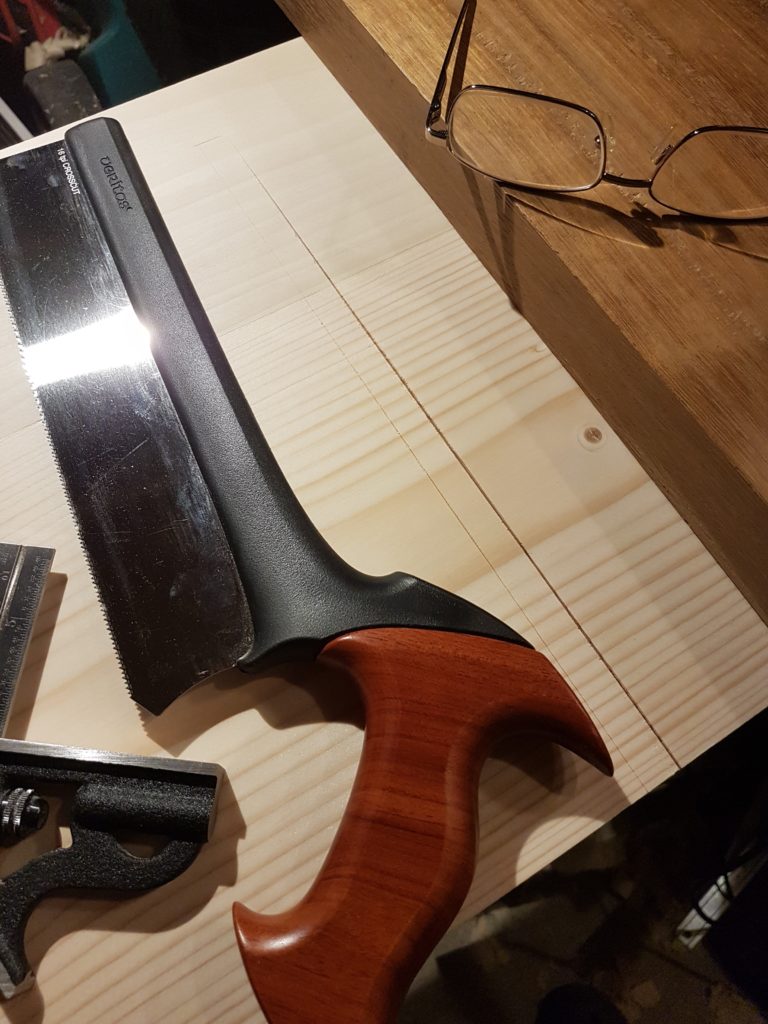

Dovetail saw

Don’t skimp here, find a dovetail saw that is really comfortable in your hand, well balanced and has a fine set tooth (14 to 20 tpi).

I like the Veritas fine-tooth dovetail saw, but there are some really fantastic saws out there from brands like Skelton, BearKat Wood, Pax, Lie-Nielsen, Bad Axe and Rob Cosman. Find what works for you and stick with it. Once you become accustomed to a saw and develop your muscle memory, you don’t want to go changing it very often.

Fretsaw

The humble fretsaw is a bit timesaver when hand-cutting dovetails. Once you’ve done the rip cuts with your dovetail saw on both pins or tails, you can cut out most of the waste quickly with a fretsaw (just make sure you don’t cut the tail or pin off). My fret saw is just a cheap basic one, but I always use top quality Pegas blades. It doesn’t need a wide throat, just twist the blade to somewhere between 45° and 90°.

½” Chisel

When you’re starting out you don’t need a huge selection of chisels, you can get by with just one. ½” (12mm) is a good size, and is the most often used chisel so start your collection there. But get a really good bevel edged chisel and never open a paint can with it.

I like Lie-Nielsen bevel edge socket chisels because their side bevels come down to form a narrow side, they sharpen easily and hold their edge well. They’re a direct copy of the original Stanley Sweetheart 750 bevel edge chisels, which Stanley have recently restarted making.

Obviously a full set of chisels is going to be more useful, but you can get away with just one. I have two sets of 5 chisels. One set comprises ⅛”, ¼”, ½”, ¾” and 1” and their bevels are ground to 30° and the micro-bevel is polished to 35°. I use them for hardwoods. The other set is metric and comprises 3, 6, 12, 19 and 25mm, their bevels are ground to 25° and the micro-bevel is at 27°. I use these for softwoods.

Mallet

The choice of mallet is very much a personal one. My favourite is the Veritas Journeyman’s mallet, which is round and has a brass head. I also have a traditional English square-headed beech mallet, but I find it a bit cumbersome. Other woodworkers like round mallets made from dense hardwoods like Lignum Vitae. Find one you like and get along with, it will last you a lifetime and become an extension of your arm.

#4 smoother bench plane

The #4 smoother bench plane is the one everyone thinks of when they think of woodworking. It’s been super popular with woodworkers for a very long time because it’s an almost ideal balance of weight, length and width. The standard 45degree frog will suit most woods and you’ll get a good finish with minimal tear-out if you tune it up properly.

A couple of years ago I switched from my grandad’s old Stanley #4 handyman, to a brand new Stanley Sweetheart #4. My modern Stanley is excellent. But after reading reviews about it I’ve been lucky, as many have problems. It has a fixed 45 degree frog, Norris style adjuster, ⅛” thick blade, thick chip-breaker and an adjustable throat.

I’ve found the plane iron to be nice quality, it sharpens well and holds its edge. The base on mine is flat and square to the sides, but some of the reviews I’ve read have reported issues with the base being out of flat and not square to the sides.

Don’t buy a cheap plane, you’ll find it super frustrating and it may well be the cause of you giving up on woodworking. Good brands for new planes include Lie-Nielsen, Veritas, Clifton, Qiangsheng Luban and Wood River.

If you want the satisfaction of using an old plane that you’ve refurbished yourself then go for an old Stanley Bedrock pattern, that’s the one with the squared off tops to the sides. These old Stanleys are widely recognised as being the pinnacle of Stanley’s production and are highly sought after (so be prepared to pay even for a ratty one).

Essential power tools

- Track or plunge saw

- Drill / driver

- Router

Track or plunge saw

Having used a track saw for a few years now, I would say that it’s the most cost effective, accurate, safe and versatile way of breaking down materials. My track saw is an entry-level own-brand model, and it’s fantastic. It doesn’t appear for sale under the same brand name anymore, but identical saws are available with different brand names. I suspect they all come out of the same factory.

Drill / driver

I don’t use a lot of screws in my projects, but I need to sometimes. A good quality cordless drill/driver with a torque limiter is an excellent addition to your toolbox.

I’ve found that there is an enormous difference in quality of drill bits, and if you want a clean hole, buy the best drill bits you can afford. I try to buy Fisch drill bits whenever I can; they are excellent.

Router

The most versatile router is a plunge router. But there are a few fixed-base routers and trim-routers that have plunge bases as an option.

If I was starting over, knowing what I know now about routers. I would, with no hesitation, buy a great trim router and a plunge base accessory. A bigger plunge router is something you can get by without, unless you are a kitchen fitter.

Essential machinery

There are only three machines I consider for my essential woodworking toolkit, everything else is a luxury.

- Bandsaw

- Drill press

- Planer/Thicknesser (Jointer/Planer)

Bandsaw

There is so much you can do with a bandsaw. It’s one of the most versatile pieces of woodworking machinery you can own. You can cut intricate shapes with a thin blade, you can rip-cut boards, you can re-saw boards into thinner boards. You can even cut dovetails and other joinery.

If you buy a bandsaw, get the biggest you can afford. Concentrate more on its re-saw capacity than the throat. On my saw I’ve never run out of throat capacity, but the re-saw height is never enough. Get one with a cast iron table and make sure it has a standard ¾” mitre gauge slot.

Drill press

Not just for drilling holes. You can use a drill press for so much more. I’ve seen them used as a vertical lathe, as a bobbin sander and even as a slot cutter. I have a bench-top model and I find it very frustrating. The reach is too short, and the vertical range is way too limited.

My drill press is the next tool on my hit list for replacement. When I do, it will be for a floor-standing model with a deep throat and long quill travel.

Make sure the quill doesn’t have any wiggle room, you’ll get inconsistent holes if it moves around. Drill presses are not expensive items, especially second-hand, so make sure you get yourself a decent one.

Planer/Thicknesser (Jointer/Planer US)

There is one task that anyone who makes furniture from solid wood needs to do, and that’s prepare their materials. You first need to flatten a face, then square an edge and finally make the opposite face parallel. You absolutely can do this by hand, and every woodworker should learn how to, but it’s really slow and hard work. To speed things up, you can use machinery.

You can have a separate planer (jointer US) for making your first face flat and creating a square edge to that face. A separate thicknesser (planer US) to make the opposing face parallel to the first face. Alternatively, you can combine the two functions into a single machine. If you’re doing a lot of processing it makes sense to have both machines, but for most home woodworkers a combo machine is a much more cost-effective and space-efficient solution.

So do you go for a segmented cutter head or traditional blades? This depends on your budget more than anything. A segmented cutter head will add a lot of capital expense, but it will be quieter and give a better finish. I have a fairly cheap combo machine, with blades and it gives good results. I will hit the surfaces with a hand plane anyway, so the finish quality isn’t a factor for me. Noise may be a deciding factor for many people, especially in residential areas.

When buying a planer/thicknesser (jointer/planer US) you should also look at the quality of the fence, it needs to be sturdy and square along its length. The length of the planer (jointer US) beds is also important, especially if you want to flatten anything long.

Beyond the essential

You can make just about any furniture with the essential woodworking toolkit above. But if you want to speed up the processes, improve accuracy and broaden your scope, then the following luxuries will be of interest.

As you learn more about the kinds of woodworking you enjoy and want to pursue further, you’ll want to explore more specific tools for the tasks you’re doing.

For some tasks they’re not just luxuries, they’re essential. I’ve put them under the same headings as before, but within each heading I’ve put them in order of usefulness (in my opinion).

Luxury layout and measurement tools

- Dividers

- Dovetail marking guide

- Calipers

- Panel gauge

- Vernier callipers

- Mitre square

Dividers

When marking out dovetails a pair of dividers make the process very simple, and give you beautiful even spacings and perfectly located kerf.

Dovetail marking gauge

A 1:8 marking gauge makes marking up hardwood dovetail tails a cinch. For softwoods you may want a 1:5 or a 1:6 depending on your preference.

Callipers

When you’re turning beads on the lathe, or a tenon of a particular size, you can use callipers to test the fit as you go. Once they slip over the groove you’re at the right size.

Panel gauge

If your boards are wider than about 6” / 150mm then a standard marking gauge is going to be too short, and not have a wide enough stock to accurately mark a width.

This is where a panel gauge comes in, the long beam and wide stock give you the reach and the stability to mark wide pieces with confidence.

Vernier callipers

As I’ve said before, don’t get too hung up on exact sizes. However, a vernier calliper is great if you need to measure a drill bit, or some other tool.

Mitre square

If you’ve got a combo square, then you’ll probably never need a mitre square, but if you do a lot of mitring, then a dedicated mitre square may prove useful.

Luxury work-holding

Once you’ve got the basics of work holding down, there are lots of options and variations that will increase productivity and reliability of your clamping and work-holding.

- Sash clamps

- Panel clamps

- Moxon vise

- Holdfasts

- Toggle clamps

Sash clamps

Sash clamps can impart huge forces over a long reach, especially if they use a steel I beam or a U channel. They can also be shop-made with wooden beams, but won’t be able to put as much clamping force as a steel or aluminium extruded clamp.

Panel clamps

These are purpose designed for clamping up wide boards whilst keeping them flat and aligned. Invaluable if you make a lot of table tops or build up wide panels from smaller boards regularly.

They usually have a mechanism to clamp the boards flat as well as push their edges together. Veritas do some nice attachments that allow you to make wooden clamp bars of any length to suit your requirements.

Moxon vise

Little can beat a moxon vise for cutting dovetails. With a little bit of effort and some basic vise hardware (screws) it’s easy to make your own Moxon vise. There are a plethora of kits around for the screws, ranging from Benchcrafted at the top end of the scale through to using long coach bolts.

Holdfasts

Genuine holdfasts are wonderfully simple, just drop it into a dog hole, give it a tap with your mallet and your work is held. Tap it the other way to release. I’ve seen some attempts at screw-based hold-downs, but they’re nowhere near as effective or simple as a properly forged holdfast. Perfect for holding your workpiece when you’re chopping out dovetails, or using a router plane.

Toggle clamps

Invented by Destaco in the 1930s, the toggle clamp is great for jig making. You can set up your jigs so that work-holding is simple and repeatable.

Luxury hand tools

If you are a hand tool woodworker, then these are really going to be part of your essential woodworking toolkit. For many woodworkers machines have superseded these tools, but often they augment the machinery to provide a superior level of fit and finish.

- Jointer plane

- Block plane

- Bevel-up jack plane

- Router plane

- Shoulder plane

- Shooting plane

- Cabinet scraper

- Small router plane

- Spokeshave

- Combination plane

- Rebating (Rabbeting US) plane

- Scrub plane

Jointer plane

If you want to flatten your own stock, or make sure an edge is straight and square then this is the plane you need. A #7 jointer is the one to go for, it’s long and heavy.

Block plane

The humble block plane is a useful little tool, it comes in a variety of bed angles to suit what you want it to do. As a bevel-up plane, for difficult woods with swirly grain, a standard angle plane will help tame the tear-out. For end grain, a low-angle block plane will cut through cleanly.

I use my Veritas apron plane for all kinds of tasks ranging from knocking off an arras, to planing a bull-nose onto the end of an oak cabinet top.

Bevel-up jack plane

This bench plane is a very useful addition to your toolbox, with the bevel up blade you can grind a variety of angles to perform different tasks. No need to change the frog angle or add a back bevel.

I have several blades for my bevel-up jack, which I have at different angles, the bed on my plane is 12° so I have blades at 23°, 33° and 43° giving me effective cutting angles of 35°, 45° and 55°. The low angle is great for softwood end grain (the edge angle is a bit too low for hardwoods). The medium angle gives me a standard 45° bench plane, which I tend to use where I’ll have joinery as I don’t put any camber on these blades. The final one I use on woods where the grain is changing directions and it’s likely to tear out, but maybe not so bad that it needs a cabinet scraper.

Router plane

For joinery these are invaluable, whether it’s for a half-lap, a tenon or a stopped or through dado. The router plane can even be used to create a rebate (rabbet US).

Shoulder plane

As their name implies, a shoulder plane is used for squaring up a tenon shoulder. But, being a rabbeting plane they often also get used to take a thin shaving of a tenon cheek to aid fitting.

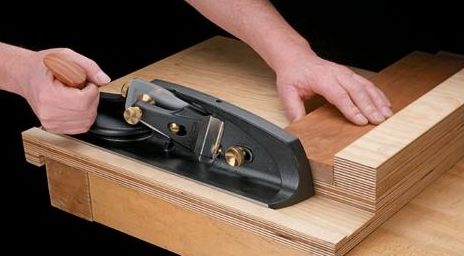

Shooting plane

This is one of my favourite luxuries, purpose designed to work in tandem with a shooting board.

This plane has a skewed blade at a relatively low angle and designed to cleanly plane across end grain. When sharpened to an appropriate angle it will slice through 6/4 white oak end grain leaving a glassy finish and a perfectly square face.

Cabinet scraper

When the grain is out of control, or heavily figured there’s nothing better than a cabinet scraper to get a smooth surface. I find it easier to control than a card scraper and the cast base helps keep your stock flat and limits the tendency to create hollows.

Small router plane

Perfect for preparing work for inlays. The small blade set at a constant depth takes much of the risk out of the process. They can also be used for cleaning up small tenons.

Spokeshave

When you are planing curved edges you need a plane with a very short sole. This is where a spokeshave comes in. The sole can even be rounded to make planing inside concave curves possible too. There are basically four different spokeshave patterns, flat, rounded, convex and concave.

Combination plane

Perfect for cutting grooves for drawer bottoms (just make sure you think about your visible joinery), the combination plane or plough plane looks really complicated, but it’s not really.

I have an old Stanley #50 and it works brilliantly, but the Veritas small plough plane, Lie-Nielsen tongue and groove plane and the Veritas combination plane are all fantastic modern versions.

Rebating (Rabbeting US) plane

There is a vast choice of rabbeting (rebating) planes available. But it depends on the kinds of rebates / rabbets you want to cut and how wide or deep the rebate (rabbet US) will be as to which will suit you best. Some have depth stops and fences, some are just a block plane or bench smoother with a blade that goes right to the edge.

To give you an idea of what you can use and where, here are a few examples.

For a raised panel door you may want to use a Stanley #10 or equivalent bench plane, but a wide shoulder plane or a rebating (rabbeting US) block plane would work too.

To cut a rebate (rabbet US) for the back of a case to sit in, something like a Stanley #78 fillister plane works well, or you can use a Stanley #50 with a wide blade. You’ll need a depth stop and a fence to make a good job. For cross-grain, engage the nicker (a small vertical knife that runs ahead of the blade) too.

For cutting rabbets across grain you’ll need to make sure your plane has a nicker to sever the fibres.

Scrub plane

If you want to hog away lots of material to flatten a board, the scrub plane is your beast. The heavily cambered blade will take a really deep cut, especially across the grain. You just need to make sure the throat is open wide enough for the shavings. It’s a very satisfying plane to use, those big thick curly shavings come out like potato chips. I ground a blade to fit my jack plane, moved the frog back, and it works wonderfully.

For a nice rustic effect you can run the scrub plane across the board in one direction and then rotate through 30°-90° and plane away again. It leaves an attractive, but subtle, rippled diamond pattern which feels lovely when sanded smooth.

Luxury power tools

These power tools will speed things up, and can perform some tasks you just can’t do quickly any other way. They’re not essential though, and you can get away without ever owning them.

- Joinery power tools

- Random orbit sander

- Jigsaw

- Oscillating multi-tool

- Brad nailer/stapler

- Belt sander

Joinery power tools

There is a range of joinery power tools available, ranging from cheap basic biscuit jointers to the truly game-changing Festool Domino.

I use a biscuit jointer more for alignment of workpieces when gluing up, than I do for any strength in a joint. They’re great for fitting face frames. I don’t think the tenon (biscuit) is embedded deep enough to be of structural use, but they are fairly strong.

Dowel jointers and dowel jigs create strong joints if they’re well fitting. But they are hard to align accurately.

Then there’s the Festool Domino, essentially a slip-tenon machine. It’s simple to use, accurate and versatile. If I had the budget, and I was going to buy a joinery power tool, this is the one I would get.

Random orbit sander

I don’t like sanding, it’s dusty and makes a huge mess everywhere. Recently I’ve started buying mesh sanding disks, and they have transformed my random orbit sander. Now the dust extraction actually works.

A random orbit sander will speed up final surface preparation, if you’re sanding at all. You can go through the grits much more quickly than by hand. Then you can just do the final grit by hand if you’re looking for a great finish.

Jigsaw

If you need a portable saw that you can use to scribe an irregular shape, the jigsaw is the tool for the job (assuming you don’t want to do it by hand).

Oscillating multi-tool

The blade/saw/sander oscillates side-to side, giving a forward facing cutting edge. These gizmos are useful in many ways. I’ve used one to cut a slot to take a piano hinge edge-on in a box side. I’ve used them for cutting away architraves to tile underneath them, and I’ve used it for cutting into plasterboard (drywall US).

Brad nailer/stapler

If you have a compressor, then a brad nailer or stapler is a very useful addon. Great for knocking up shop-made jigs, fitting beading and cornices, and temporary clamping blocks. The nails are weak, but they’re driven in so fast the piece doesn’t have any chance to move, they’re great when used in conjunction with glue.

Belt sander

I have a love-hate relationship with belt sanders, they’re very aggressive and generate huge amounts of dust. But, if you need to sand something aggressively and don’t mind the dust, then they’re great workhorses.

Luxury machinery

For me, machinery should be there to do the mundane tasks that are time consuming. They need to be accurate, and capable of performing those tasks repeatedly without change.

- Router table with lift

- Table saw

- Chisel mortiser

- Lathe

- Compound mitre saw

- Compressor

- Bobbin sander

- Disk sander

- Drum or wide belt sander

- Spindle moulder / Shaper

- Slot mortiser

Router table with lift

I have a router table without a lift, and it’s like having an arm without a hand. You want to easily and accurately adjust the depth of your cut at the router table. That way you can dial-in the fit of whatever it is you are routing. Your router table should also have a ¾” standard mitre slot, so you can use a good quality mitre gauge.

There is so much you can do with a router table. With a little thought it can replace many of the functions you would normally need a table saw for. With the right router bits you can raise panels, cut rabbets (rebates), cut dadoes, make tenons, route around patterns and make cope-and-stick frames.

Table saw

Many people will be shocked that I’ve put a table saw so far down the list. The reason is that I just don’t find them that useful. In the UK we don’t have stacked dado sets because of some weird European health and safety rules. The crown guard and riving knife make crosscut sleds either impossible or require using it without the crown guard, which is also not allowed in a commercial workshop.

If you have both the budget and the room for a table saw, they can be a useful addition to your workshop. But you need a really good one. Don’t bother with a job site saw, or contractor’s saw. The only kind worth the space and expense is a cabinet saw. That’s one where the motor, trunnions and blade are mounted to the cabinet, and the top is separate (but attached to the cabinet).

Features to look for when buying a table saw are: You want the mitre slots to be ¾” standard, check that they’re parallel to each other. The throat plate should be removable and a standard thickness so you can make your own zero-clearance inserts. The riving knife should be coplanar with the blade, and remain coplanar throughout the full range of blade movement. The top of the riving knife should also sit at or below the crown of the blade so you can use a crosscut sled. The blade should be 10” / 250mm or bigger. The mitre gauge should be solidly made, and have a width-adjustable runner to reduce slop.

The rip fence should be micro-adjustable and have graduations in both metric and inches. The rip fence should also be adjustable for squareness and parallel to the blade. It needs to be possible to clamp accessories to the fence. The inch gradations should be 4-R (fractional) increments, and not in 1/10 or decimal increments.

In an ideal world you want a crown guard that’s not attached to the riving knife, but instead is fixed to an arm above the saw so you can use the guard and it’s dust extraction with a crosscut sled.

If you can get a dado stack for the saw, and the arbor is long enough to take one, then definitely do get one. It’s allowed in Europe if you have an overhead crown guard.

My table saw used to have a sliding table, but I found that to be more trouble than it was worth and took it off. The sliding table just seemed to make everything inaccurate and had too many variables to make its fence reliably square and the slide run parallel to the blade.

Chisel mortiser

Some believe these to be witchcraft because they let you drill a square hole. Great if you like to use mortise and tenon joinery, but don’t want to spend the time chopping out mortises by hand. With a sacrificial bed you can easily and accurately cut through tenons. Get one with an indexable table to make life even easier.

Lathe

If you need to do more than make the occasional drawer knob, or you want to get into the wood-turning side of the craft a lathe is a very useful addition to your workshop. I have a fairly small lathe, which I’ve used for all kinds of projects ranging from drawer knobs, screwdrivers, pens, candlesticks and even bench dogs.

Compound mitre saw

I find these good for making repeated, consistent cross-cuts of long material. So let’s say you want to chop an 8’ / 2.4m board into 6” / 150mm sections then this is the beast for you.

On a table saw or MFT with a track saw it’s a bit of a pain (although not too bad on an MFT), but with a mitre saw it’s just set a stop block and then chop, chop, chop. The compound mitre saws usually have a wider reach, and can also cut at various angles, so I wouldn’t bother with a plain chop saw.

Compressor

If you want to use a brad nailer, or any other air-powered tools, then you’ll need one of these. If you’re just brad-nailing then you don’t need a large reservoir (1.5gal / 5l is enough), but for spraying finish or any rotary tools (drill, driver, torque-driver) you’ll need at least 13gal / 50l.

Bobbin sander

If you make lots of things with inside (concave) curves, then a bobbin sander is useful. If you make them occasionally, then use a sanding drum on your drill press, or a round bottom spokeshave and spend your money elsewhere. I’ve used bobbin sanders, but never owned one and never felt the need to own one.

Disk sander

A disk sander can be a useful addition to your workshop, they’re handy for squaring up cuts, rounding outside or convex curves at a set angle to the face. You can glue sandpaper to a bowl blank and use your lathe as a simple shop-made disk sander, but if you’re using it for production work, the better ones have accurate cast tables and good dust extraction.

Drum or wide belt sander

If you’re working difficult woods or have laminations with grain going in all directions then a drum sander is going to give you a good finish. A drum sander is a bit too slow for any large scale work, which is where the wide belt sander comes into its own. They can very accurately and quickly bring difficult woods down to specific dimensions.

Spindle moulder / Shaper

The spindle moulder is the big brother of the router table, the cutting head is often configurable to hold a variety of cutters. Some cutters are complex and have many curves to make things like coving and crown mouldings, others are configured to make box joints. Get some safety training if you’re going to use one of these, they can be very dangerous.

Slot mortiser

This is like a giant Festool Domino, for cutting slots for slip-tenon mortises. With the advent of tools like the Domino these have become largely redundant, except in a commercial workshop.